filed in What Gets Me Through the Day

George Eliot Explains Why I Hate Romantic Comedies

One of my all-time favorite writers, George Eliot, born Mary Ann Evans on this day in 1819, published an essay, Silly Novels by Lady Novelists, in which she expresses the essence of what drives me crazy about romantic comedies. Eliot wrote this during the Victorian era, so you’ll have to make some adjustments. But it’s worth it. Here’s an excerpt.

One of my all-time favorite writers, George Eliot, born Mary Ann Evans on this day in 1819, published an essay, Silly Novels by Lady Novelists, in which she expresses the essence of what drives me crazy about romantic comedies. Eliot wrote this during the Victorian era, so you’ll have to make some adjustments. But it’s worth it. Here’s an excerpt.

“Silly Novels by Lady Novelists are a genus with many species, determined by the particular quality of silliness that predominates in them — the frothy, the prosy, the pious, or the pedantic. But it is a mixture of all these — a composite order of feminine fatuity, that produces the largest class of such novels, which we shall distinguish as the mind-and-millinery species. The heroine is usually an heiress, probably a peeress in her own right, with perhaps a vicious baronet, an amiable duke, and an irresistible younger son of a marquis as lovers in the foreground, a clergyman and a poet sighing for her in the middle distance, and a crowd of undefined adorers dimly indicated beyond. Her eyes and her wit are both dazzling; her nose and her morals are alike free from any tendency to irregularity; she has a superb contralto and a superb intellect; she is perfectly well-dressed and perfectly religious; she dances like a sylph, and reads the Bible in the original tongues. Or it may be that the heroine is not an heiress — that rank and wealth are the only things in which she is deficient; but she infallibly gets into high society, she has the triumph of refusing many matches and securing the best, and she wears some family jewels or other as a sort of crown of righteousness at the end. […] She is the ideal woman in feelings, faculties, and flounces. For all this, she as often as not marries the wrong person to begin with, and she suffers terribly from the plots and intrigues of the vicious baronet; but even death has a soft place in his heart for such a paragon, and remedies all mistakes for her just at the right moment. The vicious baronet is sure to be killed in a duel, and the tedious husband dies in his bed requesting his wife, as a particular favor to him, to marry the man she loves best, and having already dispatched a note to the lover informing him of the comfortable arrangement. Before matters arrive at this desirable issue our feelings are tried by seeing the noble, lovely, and gifted heroine pass through many mauvais moments, but we have the satisfaction of knowing that her sorrows are wept into embroidered pocket-handkerchiefs, that her fainting form reclines on the very best upholstery, and that whatever vicissitudes she may undergo, from being dashed out of her carriage to having her head shaved in a fever, she comes out of them all with a complexion more blooming and locks more redundant than ever.”

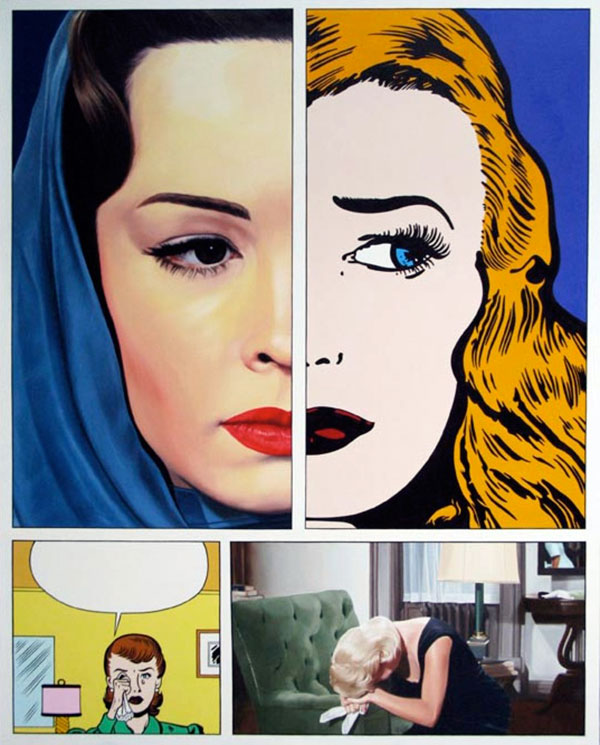

Image by McDermott and McGough

Discussion

No comments for “George Eliot Explains Why I Hate Romantic Comedies”